Erik

Chicken Coops Part II

It looks like the chicken coop is going to happen. We’re going to be renting an excavator this spring to finish up the landscaping, yard, and driveway, and we’ve cleared a spot for the coop. I’m going to teach summer school in order to have a chicken coop budget…

In other news, after I posted my plans for my coop, I got a couple of interesting responses.

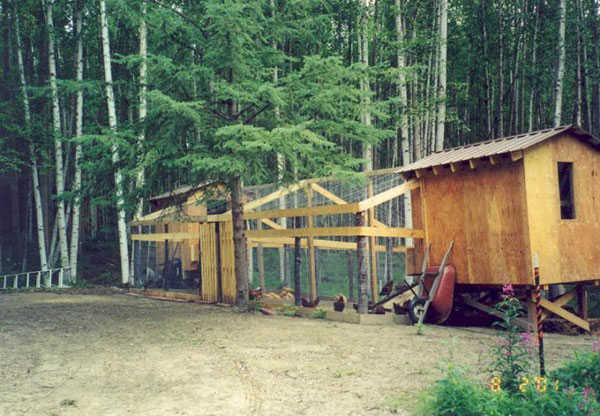

The first is a narrative from Denny Reiter from Washington state. The document is really large, but it’s a great narrative of building his beautifully-crafted coop.

The second is a narrative from Steve McGroarty that was published in the Ester Republic many years ago. He lives in the Fairbanks region (which is much colder than down here in south central AK), and his experiences provide an amusing narrative. It’s printed below. (Thanks Steve!)

“We had talked about getting chickens for years. We had discussed what breeds and how many birds to get, meat birds vs. laying hens, whether to keep a rooster, where to build the coop, and that is where it always ended …. “the coop”. We couldn’t exactly run out and bring home a herd of chickens without a corral to put them in, could we? I’m pretty good at planning to do things and really good at designing things to build, but what I’m the absolute best at, is not building things.

I won’t go into detail about all the coops that I didn’t build, but suffice it to say, that I didn’t build some pretty nice chicken coops over quite a few years. In fact, I think that I didn’t build my first chicken coop way back in the mid-eighties when we were just starting to not build our first home up on Murphy Dome. We also spent three years in Juneau and with all that rain, designing and not building a coop in Juneau is quite a bit different than designing and not building a coop in Fairbanks!

I could have gone on for years happily designing and not building chicken coops were it not for an absent minded purchase that I made some three years ago. Have you ever gone to the store and when you get home wonder why you bought certain things? Well, I did that one day at the Alaska Feed Store and when I got home I wondered where I was going to put thirty small chicks. Two wooden boxes in the storage shed solved the immediate crisis, but I knew that my days of not building a chicken coop were numbered.

Unable to postpone construction any longer, we set about designing the coop. You didn’t really think that I could actually find any of those old designs, did you? We wanted both meat birds and laying hens, so I decided to build two coops. By starting two coops, I could delay completing one a little while longer. Hey, if you had spent as many years as I had designing and not building chicken coops, you could understand my hesitancy to suddenly bring an end to all that, but the chickens were starting to fly out of the boxes in the shed and do what chickens do best, all over the shed. Some screens placed over the boxes solved the immediate crisis, but it really was time to start building the coops.

Selecting a site for your chicken coop is almost like selecting a site for all of that stuff that you stockpile for not building your compost pile; you want it close enough for easy access, but you don’t want to smell it from your deck. It should also be close enough to run electricity out to the coop.

The meat bird coop was going to be faster to build than the one for the laying hens, so we started on it first. Speed of construction was starting to become an issue. The chicks were not so small any longer, and they were starting to somehow push the screens off the boxes in the shed. Some bricks on the screens over the boxes averted another immediate crisis, but even I had to admit that the time had finally come to build the coop.

I set the coop on a post-and beam foundation so that the floor was about three feet off the ground. The theory was that this would allow a wheelbarrow to be parked immediately under the door for easy cleaning the poop out of the coop. It wasn’t until the coop was completed and in operation, that I realized that you go into and out the coop every day and only use the wheelbarrow once every week or so. The daily access to the coop necessitated stairs since it was some three feet off the ground. The stairs prevented access for the wheelbarrow. In retrospect, it probably would have been less expensive and quite a bit faster to simply place a pair of rough-cut 4×4’s on concrete blocks, compared to setting four pressure-treated 4×4’s three-feet in the ground and cross-bracing them to withstand an 8.0 earthquake.

The floor of the coop was constructed using 2×6’s and ¾-inch plywood and was 6-feet wide by 8-feet long. The plywood floor was treated with copper napthenate wood preservative. The walls were 2×4’s on 24-inch centers with ½ -inch plywood sheeting. The side-walls were six-feet high and the center of the end-walls was about 8-feet in height. After the walls and roof were up, I screwed down a “sacrificial” piece of 3/8-inch plywood. Bears may go in the woods, but chickens go wherever and whenever they please and I wanted to make it easy to replace the floor when it inevitably rotted. I cut a 4-inch by 12-inch vent in the upper rear side-wall, covered the outside with 3/8-inch galvanized hardware cloth and utilized 1×4’s and a piece of plywood to form a sliding cover on the inside of this vent. I was then able to regulate the temperature and ventilation in the coop by adjusting how much of the vent was open. I located two horizontal 2×4’s in the back of the coop with a panoramic view out the window of the almost-built compost pile. With the construction of a small “chicken-door”, the coop was done. None too soon either as the chicks had started growling at me whenever I went in the shed for a tool.

The floor of the coop was constructed using 2×6’s and ¾-inch plywood and was 6-feet wide by 8-feet long. The plywood floor was treated with copper napthenate wood preservative. The walls were 2×4’s on 24-inch centers with ½ -inch plywood sheeting. The side-walls were six-feet high and the center of the end-walls was about 8-feet in height. After the walls and roof were up, I screwed down a “sacrificial” piece of 3/8-inch plywood. Bears may go in the woods, but chickens go wherever and whenever they please and I wanted to make it easy to replace the floor when it inevitably rotted. I cut a 4-inch by 12-inch vent in the upper rear side-wall, covered the outside with 3/8-inch galvanized hardware cloth and utilized 1×4’s and a piece of plywood to form a sliding cover on the inside of this vent. I was then able to regulate the temperature and ventilation in the coop by adjusting how much of the vent was open. I located two horizontal 2×4’s in the back of the coop with a panoramic view out the window of the almost-built compost pile. With the construction of a small “chicken-door”, the coop was done. None too soon either as the chicks had started growling at me whenever I went in the shed for a tool.

The big day had finally arrived. The coop was completed and we transferred the now five-pound chicks to their new home. Never having experienced any space larger than their wooden boxes in the shed, they all immediately ran to a back corner of the coop and refused to use the roosts. A week later they were still “roosting” in the back corner of the coop on the floor. I built an access ramp so that the chickens could walk up to the roost. They wouldn’t use the ramp. We resorted to going out to the coop each night to pick up and place each of the thirty chickens on the 2×4 roosts. Fortunately for us, the chickens liked the view out the window and after a few nights of “training”, would race up the ramp to get the best spot on the roost. Another crisis solved.

While all this chicken training was going on, we were building the chicken yard. The yard is about 16-feet x 16-feet. We hoped to build the yard so that the chickens stayed in the yard and all manner of animals that dug, walked or flew (and liked to eat chickens) stayed out the yard. We treated the bottoms of some fire-killed spruce poles for fence posts. After setting the corner posts, we strung a string around the perimeter to locate additional posts and where the actual fence was going to be. To prevent the “four-legged diggers” from going under the fence, my dad pounded two-feet lengths of rebar every three inches along the entire outside fence line. I will leave it to you to calculate how much rebar this required. We tacked a five-feet high strip of chicken wire all round the perimeter of the yard to keep the chickens in and went over this with a strip of 2-inch x 4-inch welded wire fencing to keep the determined four-leggeds out, namely Sockeye, our husky-shepherd mix. We then installed rough-cut 1×6’s along the base, the top of the welded wire fencing and at the tops of the posts. To attach the wire to these boards we used countless horseshoe nails that were just small enough that you couldn’t start them without smashing your fingers about every twentieth nail. A couple of rough-cut 4×4 posts to support a 4×4 ridge beam and we could now cover the entire yard with chicken wire to complete the carnivore proofing.

Another big day had arrived for the chickens. We opened the chicken door, and they refused to come out into the yard. We opened the main door, and they walked up the edge of the floor and looked down into the yard. We built a chicken access ramp from the coop down to the yard and those smart chickens having learned how to use the ramp to get to their roost, proceeded to march down the ramp into the their new yard.

The coop and yard for the laying hens was a mirror image of the meat bird coop except for it being super-insulated. The floor was insulated with six inches of fiberglass insulation. The walls had four inches and the ceiling had six inches. After installing a vapor barrier, I added a one-inch layer of foil-covered foam insulation and covered this with 3/8-inch plywood. The main door, chicken door and sliding vent were all insulated with foam. A four-unit laying box was built and screwed to the wall about three-feet off the floor of the coop. Each unit was about one cubic foot in size. Having learned my lesson in the meat bird coop, I installed an access ramp to the roosts. I ran the ramp close to the laying box but didn’t run it all the way to the floor to make cleaning the floor easier. The coop was now ready for the ladies. The chickens thought that the top of the laying box was a great place to roost and do other chicken things. I used a pair of hinges to mount a piece of plywood to the wall above the box such that it was at a steep enough angle that the birds could not roost on it. The hinges allowed me to occasionally clean under the plywood. Another crisis was resolved and actually the slanted piece of plywood provided quite a bit of amusement for me as the chickens continued to try to roost on it!

Locating the laying box three feet off the floor reduced the chances of freezing eggs in the winter and allowed space underneath for a galvanized self-regulating water canister and a galvanized feed bucket for oyster shells. Placing these two units up off the floor of the coop on concrete blocks helps to keep them cleaner (if anything in a chicken coop can be thought of a clean) and reduces the likelihood of the water freezing. The chickens thought that this was a great place to roost and do other chicken things on the water and oyster shell buckets. I mounted a small plywood shelf under the laying box and above the buckets such that there was not enough room for the chickens to roost either above or below this shelf. Another crisis resolved.

The roof of both coops was supported by a beam, which provided a place to hang the galvanized self-regulating chicken food dispenser from a chain. We have found that by locating this on a chain, the chickens tend not to roost on it as it shifts under their weight and they apparently don’t like this. Locating the bottom of the feeder about eight inches off the floor provides easy access for the intake-end of the chickens and they tend not to scatter their feed quite as much.

We ran two electrical circuits from the house to both coops. One circuit is run to a switch located next to our back door and allows us to easily turn on lights inside and outside both of the coops. It is a really convenient system and well worth the extra effort to install. The second electrical circuit provides power to electrical outlets located in both coops. We have a 100-watt regular light bulb on a timer to provide 12-hours of light in the coop during the winter. When we rustle up a fresh herd of meat birds in the spring, it can still get cool at night, so we need to be able to use a 500-watt heat lamp on a thermostat. I was told that if you use the red heat lamp the chickens tend not to peck at each other quite as much. We use a similar set up in the laying coop to keep the water (and birds) thawed during the winter. Through trial and error, I discovered that for a given location and setting on the thermostat, I could adjust the sliding vent cover to maximize ventilation and thereby minimize the ammonia buildup that results from the out-put end of the chickens, while still keeping the water thawed. I have been able to calibrate the sliding vent and used a magic marker to mark the proper amount of opening for –20, -10, 0, +10 and +20 degrees. During the spring and fall when the chickens want to get out in the yard, but day-time temperatures are below freezing, we open the small chicken door, but close the vent. This prevents all the warm air from flowing up and out of the coop, which results in a frozen water container every time we forget.

This is our third winter with birds. Our coop seems to comfortably handle about 12 to 16 chickens. We get more fresh eggs than our family can use and have found that by selling the extras, we not only pay for the food and electricity, but the original cost of the coop construction should be paid back in only fifty or sixty years.

With both coops and yards finished, the chickens were happy and I was able to return to what I am really absolutely best at… not building the addition to our house, but that is another story.”

Winemaking with ingredients from Costco

This winter I’ve been experimenting with small batches of wine from ingredients I’ve found at Costco. Some of the experiments are definitely…experiments…but we’ve had some pretty good success too. Below are my winemaking notes for one gallon batches of the wines I’ve tried:

From left to right: pineapple wine, mixed berry wine, peach wine. (The peach is still cloudy because it's still so young.)

Mixed Berry Wine:

- 3 lbs Costco frozen mixed berries

- 3 1/2 lbs sugar

- 1 lbs raisins

- Bordeaux or fruit wine yeast

- 1/2 tsp pectin enzyme

- 1 1/2 tsp yeast nutrient

- 1 gallon water

Notes:

This is a fantastic table wine. We haven’t been able to keep a gallon of this around for more than a couple months because it tastes so good. The raisins give the wine some much-needed body, but it still has a muted, somewhat-sweet berry flavor. This would be a great table wine to serve to guests. We’ll be making a 5 gallon batch soon for this purpose. And the best part (with all these wines) is that once you have the brewing supplies, the cost of the actual ingredients comes out to $3 a bottle or less. That’s hard to beat for handcrafted, sulfite-free wine!

Strawberry Wine:

- 3 lbs frozen strawberries, blended.

- 3 1/2 lbs sugar

- Bordeaux or fruit wine yeast

- 1/2 tsp of pectin enzyme

- 1 1/2 tsp of yeast nutrient

- 1 gallon water

Notes:

Decent wine, but it was a little astrigent when new. (It was all gone within two months, so it didn’t have a chance to age!) I’m planning on trying it again with honey. It should balance the flavors better, I think.

Pineapple Wine:

- 3 lbs of chopped or crushed pineapple and syrup

- 3 lbs of sugar

- Bordeaux or fruit wine yeast

- 1/2 tsp pectin enzyme

- 1 1/2 tsp yeast nutrient

- 1 gallon water

Notes:

This wine, when young, tasted akin to canadian-bacon and pineapple pizza — notes of both pineapple and yeast. However, it’s super strong (18% alc by volume). Because it didn’t taste good new, it’s had time to age. It’s become a little drier and less yeasty. I’ll bottle some up and see what it’s like in a year, but I don’t plan to make it again.

Peach Wine

- 3 lbs canned peachesand syrup

- 3 1/4 lbs sugar

- Bordeaux or fruit wine yeast

- 1/2 tsp pectin enzyme

- 1 1/2 tsp yeast nutrient

- 1 gallon water

Notes:

This wine is still really young, but it has good potential. The peach flavor is fairly muted, and the wine is crisp and somewhat dry. I’ll let this age a few more months, but I’m optimistic of the final product.

On the to-do list:

- Canned Pear Wine

- Maybe some fresh fruit wines as it comes into season??

- Blueberry Wine

Note:

If you don’t know how to make your own wine, go my tutorial here. Just adapt the process for these recipes.

Dreaming of chicken coops

As the snow begins to melt, my mind is turning towards…chickens. We raised 20 broilers last year, and have been enjoying eating home-grown poultry over the winter. But the boys and I really would like a few laying hens as well. We’d definitely use the eggs. Between bread crusts, veggie trimmings, and old leftovers, I think we’d have the most well-fed chickens around. Additionally, Ashlee has informed me that I may not raise the chicks in the crawlspace like I did the first few weeks of last summer. This means I’m in the market for a chicken coop.

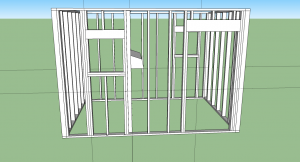

Because our summers are so short and our winters are so long, I’m going to need to have electricity in the coop for heat lamps and keeping the water from freezing. I’m thinking of building a 8′ x 12′ coop, with 4’x8′ dedicated to the laying hens. The layers will not need much space, and the additional room I’ll use for storage and raising broiler chicks in the spring.

I learned how to use Google Sketchup over the weekend, and used it to create my framing plan. Pictures are below. The program took a little bit of effort to learn, but it’s a nice (and free) drafting software for these kind of projects.

Side view looking to the west. Notice the two windows and the nest boxes that will be accessible from the storage part of the shed. *Click image for better view*.

There’s only one problem. This chicken mansion is going to cost me. Between framing, wiring, insulation, vapor barrier, etc., I’m guessing it’ll cost around $2,000 in materials. If I build it this summer, I’ll report on the final costs. These will be some very loved, expensive chickens.

The hard work of community.

I had the most interesting experience this Sunday. Our church, which is a fairly conservative flavor of Lutheranism, had a congregational meeting. At issue was whether the church should change its constitution to allow women to serve as vice-president and president of the church council.

From the outside looking in, it would appear that our church is decades behind the times. In some ways, they’d be right. But what happened yesterday was testament to the power of community and culture, and the hard work of intentionally considering our community:

I walked into the sanctuary expecting the meeting to be a quick and easy vote to change the church constitution. Of course we would allow women on the council, I thought. We filed in, signed our names on the attendance sheet, and grabbed the proposal.

The pastor started the meeting with a prayer, making some vague reference to “contentious issues.” Then the council president gave a brief run-down of the proposal.

“We found that few people are interested in council positions,” he started, “We changed the wording in these two rules to allow for women to serve as council president. Any discussion?”

The church remained silent for a minute. I figured that this vote would be nothing more than procedural. But one of the older and highly respected members of the church raised his hand.

“It’s not that I don’t support this,” he started, “but I believe that women are the heart and the center of the family. Their role is so important. I don’t want their responsibilities on the church council to take them away from that important role.”

The congregation sat in silence for a few moments, considering what had just been said.

Another respected member of the church raised his hand. “I support this idea, but are we doing this for the right reasons? If we’re only allowing women to fulfill this role because the men don’t want to do it, aren’t we just ignoring the real problem?”

Again, there was silence as the congregation considered his words.

A woman spoke up, “Here’s the way I see it. By not allowing women to serve as president, we are essentially leaving half of our talent pool untapped. Why would we do that?”

The conversation continued in much the same way for another half an hour. Each member humbly offered his or her opinion. After each person spoke, the congregation reflected on their words in a few moments of silence.

From the outside looking in, people might be shocked that a group of 21st century Americas were actually having a conversation about whether women should be in leadership roles. But from the inside, that’s not what happened at all.

On Sunday, our community came together to have a discussion. In a very authentic and intentional way, we decided how to change our culture.

The respect that had been built from decades of mutual work and experience allowed each member to talk honestly and openly. Everyone was shown respect for their opinion and words – not because it was the right thing to do, but because they had earned that respect from years of service to the community and by their evident spirituality.

Furthermore, we talked thoughtfully about how this change would affect our community and culture. Popular and homogenized culture demands that people change according to the will of the masses, but a true community examines the value and merit of changes that will affect its culture, even if their choices put them out of the mainstream.

That’s why I respect the Amish so much. They have spent centuries, as a culture, determining how new fashions, new technology, and new beliefs would affect their culture. And overall, they’ve decided the culture of the populous is not a healthy culture. Instead, they have kept the family and the community at the forefront of their values.

In the end, we did decide that women should be allowed to be council president by a vote of 42-2. It was undoubtedly the right decision even if it was a few decades late. But more importantly, we had the conversation. That’s were the hard work of community begins.

Another great day in Alaska

My brother, a friend and I took a snow-mobiling trip up north to look at a piece of property. It was a beautiful day!

Upcoming homesteading events in Southcentral Alaska (2011)

I’m planning on attending several events this spring to further my knowledge of sustainablie living in the far north. For readers in the Anchorage area, here’s a quick run-down of what’s coming up:

March 26th or April 9th

10am-4pm

Anchorage 1st Presbyterian Church

$35

Pioneers Fruit Growers Association

April 9th

1pm

Anchorage Korean Assembly of God Church

Cost: not known

Alaska Society of American Foresters Arbor Day Tree Sale

May 14th and 21st

(The 14th is the last day orders will be accepted. Tree pick-up in on the 21st)

Cost: $20 for a bundle of 20 trees.

How to Make Your Own Bacon

After a very successful experiment in bacon making, I’ve posted a tutorial on the site. A few buddies and I made 5 different types of bacon, and they all turned out fantastic. Check it out!

Another lovely quote…

“Good human work honors God’s work. Good work uses no thing without respect, both for what it is in itself and for its origin. It uses neither tool nor material that it does not respect and that it does not love. It honors nature as a great mystery and power, as an indispensable teacher, and as the inescapable judge of all work of human hands. It does not dissociate life and work, or pleasure and work, or love and work, or usefulness and beauty. To work without pleasure or affections, to make a product that is not both useful and beautiful, is to dishonor God, nature, the thing that is made, and whomever it is made for.”

-Wendell Berry from “Christianity and the Survival of Creation”

Facebook, efficient relationships, and the “performance of self”

On my Facebook page, there is a small box that proudly proclaims how popular I am. “You have 182 friends,” it states. According to Facebook, my social life is represented in 182 tiny thumbnails pictures of my “friends” and my interests in life are tidily summed up on my “Info” page.

On my Facebook page, there is a small box that proudly proclaims how popular I am. “You have 182 friends,” it states. According to Facebook, my social life is represented in 182 tiny thumbnails pictures of my “friends” and my interests in life are tidily summed up on my “Info” page.

Every morning I wake up and scan my “News Feed” where an algorithm feeds me the latest news from my 182 friends. It determines what information I should see. I scan the page in 30 seconds, quickly perusing the latest news and minutia from my 182 friends’ lives. Feeling content that I have kept up on my social connections, I grab my lunch and head out the door.

In the evenings, I occasionally load images or messages to my Facebook page. Isolated from others, I carefully curate my latest photos, deeply thinking before I assign captions and “tags.” I consider how to phrase my status update, knowing that 182 friends may see my picture or my status. This thought gives me feelings of grandeur.

My entire social life has become incredibly efficient. In a matter of minutes, I have kept up with my 182 friends. This, according to many, is the “new” way of connecting socially.

With 600 million people “connected” to one another is this way, we have to wonder whether we will eventually forget how to truly connect with each other and our community. As an MIT professor has recently said, “there is a difference between the ‘performance of self’ and ‘self.’”

I would argue that true community requires a level of both privacy and intimacy that is not possible with “social” media. I think deep down, we recognize this. When I look at my “news feed” I do not see the following status updates:

- I’m thinking of leaving my wife

- I’m lonely

- I’m grateful in an inexplicable way for the wonders of life.

- I’m not sure how to parent my kids

- We got into a huge fight

- I feel a sense of contentment and spiritual peace.

- I’m lost in life.

- I don’t know what I believe.

These are the sort of intimate details that we only share with those who are closest to us. They’re not the sort of things we share with 182 near-strangers. And so our social media is actually filled with pointless statements:

- I made brownies today

- I finished my essay

- I went for a jog today

- I love “Glee!”

At the end of the day, we think we’ve had meaningful interactions, but all we’ve really done is publicly postured our lives; all we’ve done is played the role of ourselves; all we’ve done is talked about things that don’t matter. And we’ve done it in an extremely “efficient” way. We have reduced the work of community to a few words and mouse clicks.

True community is both more public and private than this. It is messy and inefficient. In true community, we learn that living peacefully means listening more than talking. It means keeping things to ourselves. It means only allowing the handful of people into our lives who we trust.

At the same time, true community is far more public than “social media.” We cannot curate an image of ourselves when we spend time with each other. Building a house, backpacking through the wilderness, or worshipping beside one another necessitates a certain level of authenticity. We get to see each other’s true selves. This means that true community requires a certain level of vulnerability and tolerance. We find that we must show our true selves — vices and all — to our family, our friends, and our immediate community. In that sense we are vulnerable and trusting in their mutual trust of us, despite our failings. It is these interactions that create the sinews and ligaments of community. And it is these interactions that can never be recreated on a social network.